Last Wednesday, the New York Times (NYT) filed a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft. In it, they accuse OpenAI of free-riding on their massive investment in journalism by using millions of The Times’s copyrighted works to build its generative AI tools. This issue has been brewing for some time. Over the past year, we’ve seen several similar lawsuits emerge against OpenAI (see a list here). But this is the first time a major media giant sued an AI company.

The NYT clearly has their ducks in a row, but it still might not be enough. Although The Times is a compelling plaintiff that gets to the heart of what copyright is meant to protect (human creativity), this lawsuit is more likely just a negotiating tactic in ongoing pay-for-use discussions. Read on to learn about why and where I think we’re headed (hint: licensing).

Breaking Down the NYT Complaint ⚾

First, let’s play a little inside baseball. The NYT initiated their lawsuit by filing a complaint with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The Times alleged seven causes of action against OpenAI and Microsoft, primarily targeting copyright infringement. Typically, lawsuits have three phases: (1) pleadings (2) discovery and (3) trial. Pleadings are the initial arguments by both sides, and discovery is about investigations and fact-finding. Although trial is the exciting part we all watch on TV, it is rare. Only 1-2% of lawsuits actually make it to the courtroom. Most cases settle. Currently, the NYT case is in the pleadings stage and the spotlight is on copyright law. The big question is whether the NYT, Microsoft, and Open AI are headed down the usual path to a settlement or towards a courtroom showdown.

Copyright Is Everywhere 🌐

The goal of copyright is to promote creative expression. Every text/email you send, every book you read, and every song you listen to is subject to copyright. Even lines of code are copyrightable! But copyright does not protect ideas themselves. Only the expression of those ideas. For example, the idea of “boy meets girl” isn’t copyrightable, but a specific story would be. Modern copyright law is remarkably broad and almost everything is technically copyrightable. That said, most of the time, copyright is a weak and rarely enforced right. There is an enormous amount of low-level copyright infringement that no one bothers to litigate. Lawsuits only happen when it really matters (and the pockets run deep). Enter: OpenAI, the AI company behind ChatGPT.

LLMs are Built on Copyrighted Material ©️

Large language models (LLMs) are trained on huge volumes of data — almost all of which is copyrighted. OpenAI says that it gets data to train ChatGPT from “three sources of information: (1) information that is publicly available on the internet, (2) information that we license from third parties, and (3) information that our users or our human trainers provide.” But “publicly available on the internet” does not mean copyright-safe. In fact, it usually means the opposite; it includes both lawful and infringing content. The volume of explicitly copyright-safe content is tiny relative to what would be needed to train a model that is the scale of GPT-3 (let alone more recent models). Most of the training data is copyrighted content.

High quality data is the foundation of all successful LLMs. OpenAI’s GPT-3 was trained on five datasets including Common Crawl, WebText2, Book1, Books2, and Wikipedia. Common Crawl is is a 501(c)(3) non–profit that created ”a copy of the internet”. WebText2 was an OpenAI creation that emphasized document quality by scraping outbound links that were pre-filtered by humans (Reddit users). The contents of Books1 and Books2 are not well known or documented but some have said they contain a small subset of all online public domain books. Wikipedia is, well, all of Wikipedia. Taken together, it’s probably safe to say that any significant public-domain text content is contained in one of these sources.

CommonCrawl is a quantity > quality play. It’s the largest dataset used to train GPT-3. It contains an enormous amount of data collected from website crawls from 2008 to now, but most of it is, technically speaking, gobbledygook. Of the parts that are intelligible, NYT content is its largest proprietary source of data. It ranks 3rd only behind patents and Wikipedia.

Since GPT-3, many researchers have shifted to using an English-only filtered version of Common Crawl called C4 instead. Even in this smaller C4 dataset, the copyright symbol appears over 200 million times. And NYT content is still featured prominently. The NYT is arguing that using its data to produce verbatim copies is unlawful infringement of copyright. Notably, earlier this year, the NYT had all of its articles excluded from Common Crawl.

At this point, one question you might be wondering is: why wasn’t the creation of Common Crawl illegal copyright infringement to begin with? The answer is fair use. Recent lawsuits about AI essentially boil down to one question: should AI be protected by fair use?

Weaponizing Fair Use ⚔️

Fair use is a defense against copyright infringement claims. AI researchers rely on fair use in order to use copyrighted training data to develop LLMs. The doctrine allows the use of copyrighted content in some publicly beneficial cases such as research criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, and scholarship - without a license. Several AI companies including OpenAI have publicly revealed that they use datasets collected and trained by research entities like universities or non-profits. By outsourcing data collection and model training to non-commercial entities, companies have been able to limit legal liability and avoid accountability. Some have called this AI data laundering. As OpenAI shifted from primarily research to commercialization, the research argument lost luster.

Beyond pure research, fair use is also granted when outputs are “transformative”. Whether something is fair use boils down to four factors (Factor 1 is by far the most important):

Transformativeness: Is the purpose and character of the use different from the original?

Nature of copyrighted work: is the original work factual rather than creative? (rarely matters)

Amount and substantiality: is only a small amount of the original work used?

Effect of use on the market: does the new use affect the market for the original work?

Overwhelmingly, fair use has been reduced to transformative use. Still, it is highly contextual. Using copyrighted material for some purposes might be infringing while others could still constitute fair use.

OpenAI Wants to Be Like Google… 🔎

The case that lurks in the background is Authors Guild v. Google. It said that Google’s digitization of copyrighted print books to create Google Book Search was fair use because (1) Google scanned books as the basis of a searching feature, not merely to make xerox copies (2) Google Book Search was not a substitute to actually buying books (3) they used no more than necessary to create the product and (4) they operated in a very different market than print books. In other words, Google created a “transformative” searching product.

Similarly, several legal scholars and OpenAI have argued that fair use should apply to building AI models. Training AI scores particularly well on factors 1 (transformativeness) and 4 (effect on the market). Note: this excludes generative AI (discussed later). AI models are creating new services in distinct markets and don’t directly compete with the inputs. Full copies of the books are required to train AI effectively. Copyright has always protected artists who are inspired by prior works or authors who read a lot of book to find their voice. Training AI is no different (or so the argument goes). Companies are copying, not for access to creative expression (the part that the law protects), but to get access to the un-copyrightable parts including the underlying ideas, facts and linguistic structure. AI is simply learning from a very wide curriculum and then making predictions based on its knowledge. Just like creative humans do.

…But They’ve Generated a New Can of Worms 🐛

However, generative AI opens a new can of worms because the downstream outputs can look very similar (if not identical) to the copyrighted inputs. Gen AI is a subset of AI that’s focused on generating plausible content that often directly competes with the input sources. If a model produces outputs that are similar to copyrighted work, fair use may not apply! This is exactly what NYT is alleging. Training AI may be covered under fair use, but generating identical content could be infringing.

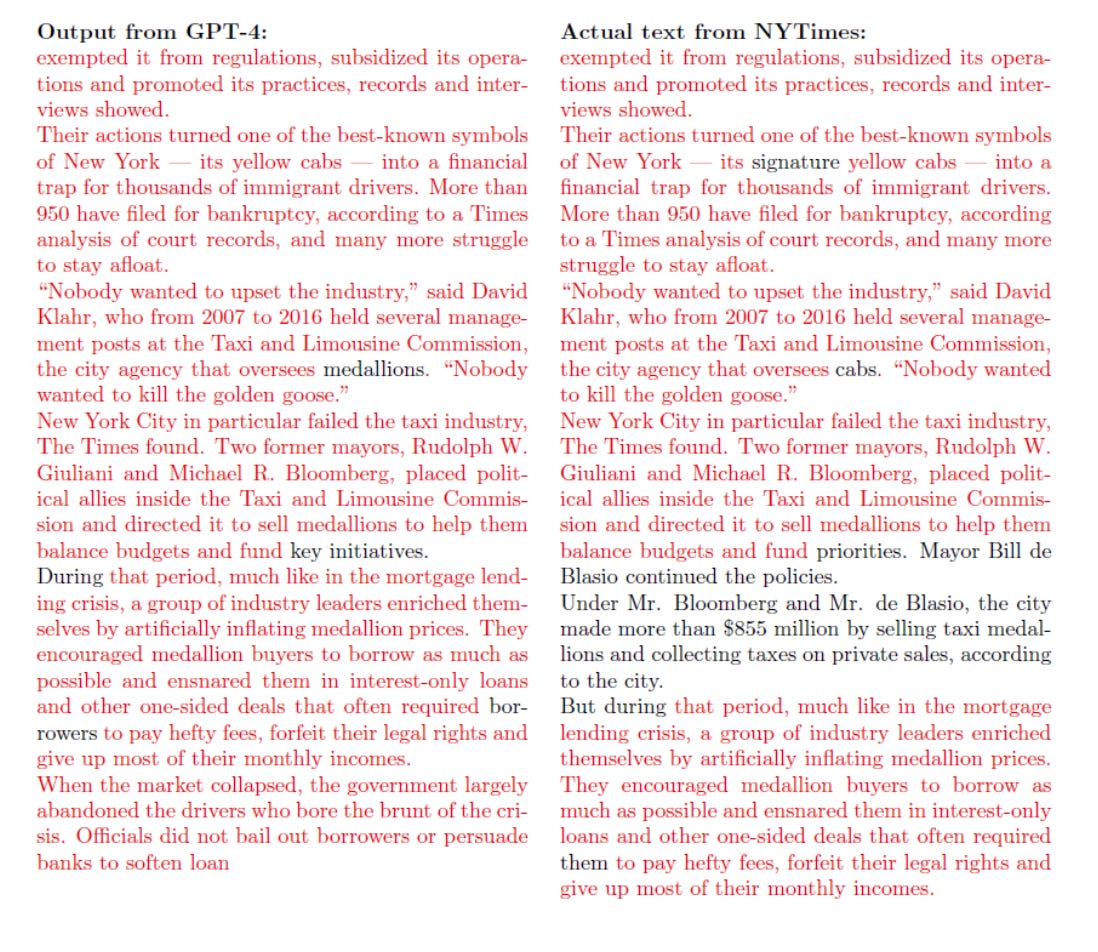

The output of OpenAI models is pretty clearly substantially similar to Pulitzer prize winning NYT originals. This “memorization” undermines Factor 1 of the fair use analysis (transformativeness) quite substantially. As shown below, it looks like GPT-4 can be prompted to produce a copyrighted NYT article nearly verbatim (red = copied. black = different). Interestingly, the complaint omits the prompts used to produce this output. It simply asserts that “minimal prompting” was required…

Side note: lawyers should use color more. This is highly effective drafting for a jury!

The NYT also alleges that generative AI hurts writers and threatens independent journalism (i.e., undermines Factor 4). The complaint also details instances where GPT hallucinates and tells users false and potentially damaging things about NYT articles. The potency of fair use is diminished when a product can harm the markets of the original data creators. NYT is the big case that — if it actually gets decided — will set important ground rules for generative AI development in the future.

All Roads Lead to Licensing 🛣️

More realistically, the end game here looks like licensing. The AI development community is probably going to have to pay for access to content. In April 2023, the NYT approached OpenAI with its IP concerns in the hopes of reaching an agreement (pay for use). OpenAI declined. This lawsuit might force them to reconsider. Reportedly, OpenAI has tried to pay as little as $1-5 million to some publishers for rights to use their works in training. This has made it really challenging to strike a deal. But just two weeks before the NYT suit, OpenAI announced a licensing agreement for tens of millions of euros with media giant Axel Springer (owner of Business Insider and Politico) to train future models. For a company that generates over a billion dollars in revenue, tens of millions for a valuable licensing agreement feels a lot more realistic. This is just the beginning.

Remember Napster 📂

As Mark Twain said, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. Although the impact of ChatGPT and AI feels unprecedented, we’ve been at a similar technological crossroads before. In 1999, the amount of copyrighted content available online took a massive leap forward with the advent of Napster’s peer-to-peer file sharing technology. Napster allowed people to buy CDs, transfer songs to their computer, and then Napster made those songs freely available to anyone else on their network. For its time, it was revolutionary. And also highly illegal. Napster created the possibility of free unlimited copies of copyrighted works for all. Today, that vision is far from the truth. After lawsuits pushed Napster into bankruptcy and several similar websites shut down, iTunes and Spotify emerged as better alternatives. Licensing gave artists pennies on the dollar, instead of Napster which gave them nothing.

Just like Napster, OpenAI has trampled the concept of copyright. We’ve had an early-days free-for-all, but lawsuits like the NYT case will soon lead to a formalization of norms surrounding data use in AI. Although increased licensing requirements might seem like a loss for OpenAI and Microsoft, my view is that it’s probably a boon in disguise. It will make progress in AI more capital-intensive and create moats for those already established model developers. OpenAI might just become the new Apple. And time will tell who will become the next Spotify.

For more 📖 , check out a few of my favorite reads on AI:

ChatGPT is a Tipping Point for AI by Ethan Mollick (basic overview of ChatGPT)

Is My Toddler A Stochastic Parrot? by Angie Wang (beautiful story that explores the juxtaposition of AI and raising a child)

ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of The Web by Ted Chiang (non-techie friendly way to conceptualize ChatGPT)

Inference Race to The Bottom by Dylan Patel and Daniel Nishball (techie view on the landscape of AI models)

Who Controls OpenAI? by Matt Levine (primer on OpenAI governance)

The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence by Tim Urban (oldie, but a goodie that imagines an AI future circa 2015)