To Be or Not To Be (A Security)

That is the question underlying SEC v. Ripple and the crypto industry.

If you follow news in the cryptocurrency world, chances are you’ve heard of last week’s fiasco: $BALD. “Bald” is a memecoin that was created to mock Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong’s lack of hair. It surged in value after launching on the new Ethereum Layer-2 network called Base. However, within 48 hours, it became clear that Bald was a rug pull – a deceptive scheme in which developers launch a token, make it seem legitimate, and then suddenly remove liquidity, leaving investors with significant losses. In this case, the deployer of Bald removed $25 million in liquidity, causing the token's value to plummet by 90%. Investigations after the fact revealed ties to Alameda Research, leading some to speculate that Sam Bankman-Fried is somehow linked to Bald. As of now, it’s mostly speculation, but the situation has left investors disappointed and regulators unsettled.

Unbacked crypto assets have little, if any, intrinsic value, and their price volatility exposes consumers to the potential for enormous upside or downside. While 2023 hasn’t been crypto’s year, the Bald fiasco serves as a timely backdrop to highlight the vulnerabilities that arise when there is a lack of a legitimate regulatory framework. This article unpacks crypto regulation in light of the recent SEC v. Ripple ruling.

Laying a Foundation: What Are We Talking About?

Crypto is a set of ideas and products and technologies that grew out of the Bitcoin white paper. Though the term “crypto” may suggest a focus on currency, the reality extends far beyond that (recall Bald). Crypto has evolved into a vast landscape envisioning a decentralized future for the World Wide Web, incorporating blockchain technology, tokens, DAOs, DeFi, dApps, and the metaverse, among other elements. I won't try to explain each concept here, but for the purpose of understanding SEC v. Ripple, crypto serves as an effective shorthand and conceptualizing it as a digital asset or currency is a fair starting point. Some of the biggest players in the crypto market include Bitcoin, Ethereum, Tether, BNB, and XRP. In particular, XRP will be important when we get to SEC v. Ripple.

A Modern Classification Problem: Security or Commodity?

A key question for the industry is whether a specific cryptocurrency is a security or not. Classification depends on the individual digital asset and the context. This means that some crypto may be deemed securities, while others are not. This classification is critical because it impacts who regulates a digital asset and what regulations apply. Securities are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and face heightened regulations on price, reporting, and greater general oversight under US federal securities laws. Commodities are overseen by the Commodity Futures and Trading Commission (CFTC) which tends to impose less stringent regulations. The two regulators are engaged in an ongoing turf war over who gets to regulate what. It’s a classification battle between securities (SEC) and commodities (CFTC).

SEC, Securities, and the Howey Test

A security generates a return from a common enterprise - like shares in a company that trades on the stock market. The term includes an "investment contract," as well as other instruments such as stocks, bonds, and transferable shares. In 1946, the Supreme Court established a three-prong test to determine whether a financial instrument will be considered an “investment contract,” and therefore, a security. The Howey test defines an investment contract as a "contract, transaction[,] or scheme whereby a person:

Invests his money,

In a common enterprise; and

Is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or third party.”

The analysis emphasizes economic reality and the totality of the circumstances surrounding the sale. Most cryptos fail on Howey’s 3rd prong because they rely on decentralization principles.

Though the original test was designed to be flexible to protect investors, it was based on a case about orange groves in 1946. The test predates digital asset technology itself. Regulators need to recognize that cryptocurrencies are a unique breed of products and technological infrastructure that differ significantly from traditional financial products. Applying old laws to new tech won’t do. Earlier in July, Senator Lummis (R-WY) and Senator Gillibrand (D-NY) reintroduced the Responsible Financial Innovation Act to establish clearer bright-line rules for what is a security and what is a commodity (we’ll have to wait and see what Congress does with this).

Recent increases in SEC crypto enforcement actions indicate the agency’s heightened focus on asserting regulatory authority over cryptocurrencies as securities. SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has advocated for most cryptocurrencies, excluding Bitcoin, to fall under securities laws. In contrast, crypto enthusiasts have been advocating for the market to be classified as a commodity market in order to leverage the more favorable regulatory environment in that category.

CFTC, Commodities, and Store of Value

Commodities are physical goods that are “stores of value.” Think of lumber or gold. As cryptocurrencies have emerged as stores of value, the CFTC has declared that certain digital assets are commodities and asserted jurisdiction over them under the Commodity Exchange Act. While the SEC and CFTC have differing views on cryptocurrency oversight, they agree on some classifications. For example, both view Bitcoin as a commodity because it is a decentralized currency that doesn’t produce returns from a common enterprise. In other words: it fails the Howey test.

The SEC Sued Ripple

A recent ruling in SEC v. Ripple has sent shockwaves through the crypto industry. The case revolves around the legal classification of XRP, the digital asset associated with Ripple Labs. Ripple is a software company that specializes in crypto solutions. It builds products on the XRP ledger which is an open source, decentralized, and permissionless blockchain. Unlike Bitcoin, Ripple does not rely on miners, and all 100 billion XRP tokens were created at the network's inception in 2012. The company raised funds for its global payments network by selling XRP tokens to institutions such as banks and hedge funds, conducting open-market transactions, and distributing tokens as a form of employee compensation. Importantly, Ripple did not register its offerings or file financial statements with the SEC.

XRP Tokens Themselves are Not Securities…

In December 2020, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Ripple Labs, alleging that the company unlawfully sold over $1.38 billion dollars worth of XRP tokens in violation of Section 5 of the Securities Act. The SEC argued that XRP was a security because Ripple sold XRP tokens to fund its project (like a stock). Ripple argued the opposite.

Judge Analisa Torres found that XRP, as a digital token, is not in and of itself a “contract, transaction[,] or scheme” that embodies the Howey requirements of an investment contract (i.e., the token isn’t a security). However, she stressed that even if XRP exhibits commodity-like characteristics, it may nonetheless be offered or sold as an investment contract. This means that the subject of an investment contract can be a commodity! For instance, a capital-raising transaction where a blockchain project sponsor (like Ripple) sells a crypto asset (like XRP tokens) to finance development of the project could involve an investment contract and thus be considered a security. That’s exactly where the case went next.

…But Certain XRP Transactions Might be Securities Based on the Context

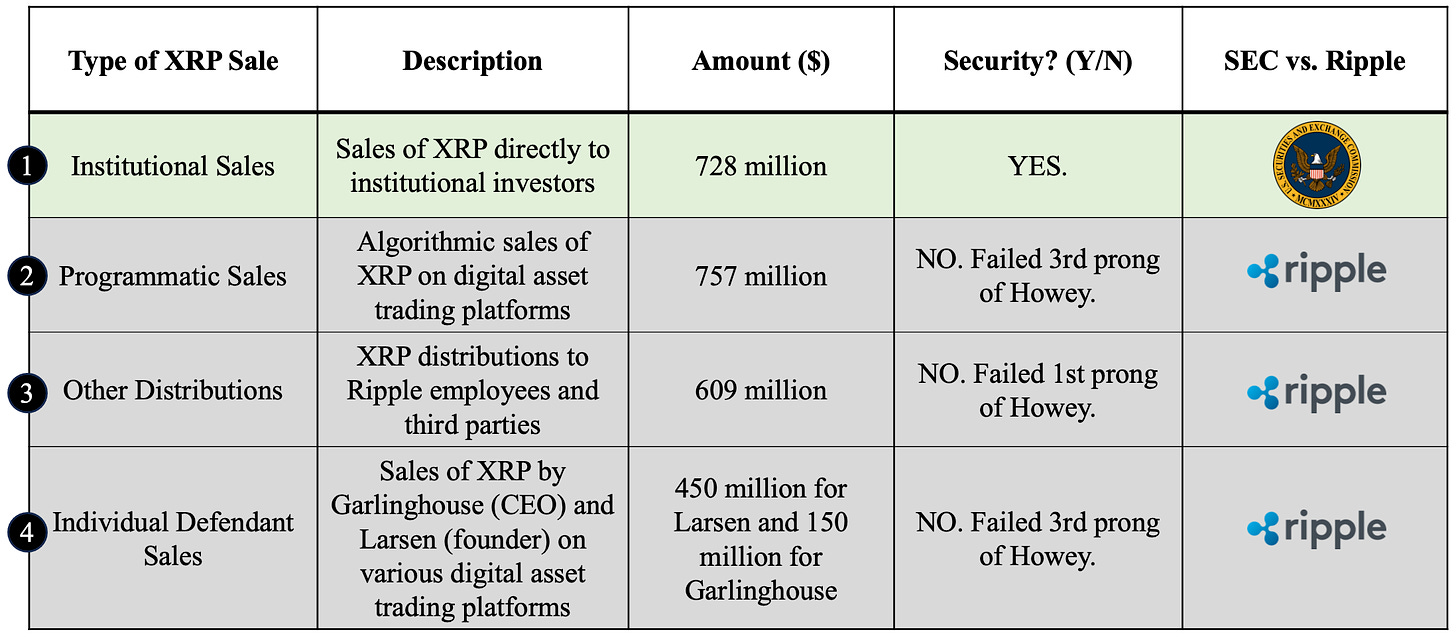

The court examined 4 types of XRP transactions: Institutional Sales, Programmatic Sales, Other Distributions, and Individual Defendant Sales. Applying Howey, only one transaction was deemed a security - Institutional Sales. This category passed the test because (1) institutional buyers provided capital in exchange for XRP (2) horizontal commonality, or pooled proceeds, existed and (3) reasonable institutional investors would expect to derive profits from Ripple’s communications and marketing. In contrast, the court distinguished Programmatic Sales based on Howey’s third prong. These sales were considered similar to secondary market purchases, because neither Ripple nor the purchasers knew each other, and profit expectations were tied to cryptocurrency market trends rather than Ripple's actions. The Other Distributions category failed the first prong of the Howey test since there was no "investment of money" from employees to Ripple; instead, Ripple paid XRP to its employees. The court quickly dismissed the issue of Garlinghouse’s (CEO) and Larsen’s (founder) offers and sales of XRP, likening them to the Programmatic Sales category. Additionally, the court rejected Ripple's fair notice defense for Institutional Sales but left open the fair notice defense for the other types of transactions. To summarize:

Sound and Fury, Signifying Nothing

For all its sound and fury, SEC v. Ripple is somewhat counterintuitive and leaves much to be desired. Ripple claimed a decisive victory on multiple fronts, with XRP tokens, programmatic sales, distributions via grants, and issuances to executives all deemed not to be securities. The SEC maintained its grip over XRP sales to institutional investors. Regardless of who "won" each aspect of the case, the overall conclusion seems to defy common public policy sense. The ruling imposes stricter regulations on sales involving sophisticated institutional investors while relaxing regulations for less sophisticated retail investors. That is backwards. Conventional wisdom prioritizes greater protection for retail investors.

The ruling highlights the persistent challenges in classifying cryptocurrencies and emphasizes the urgent need for a well-defined regulatory framework, such as RIFA. Currently, the conclusion undermines fundamental principles of securities laws, which are designed to protect investors and and promote disclosures to enhance risk assessment. Recent developments, like Coinbase re-listing XRP, have intensified pressures on the SEC and its regulation-by-enforcement strategy. In response, the SEC has signaled that it intends to appeal the Torres decision. Already, we have seen Judge Rakoff reject the Torres approach. In SEC v. Terraform, he declined to draw a distinction between coins based on their manner of sale. As the industry seeks clarity, the case for implementing bright-line rules is increasingly compelling.

This may sound counter intuitive but is consistent with first principles. Shares and debt are legal contracts and even secondary sales are regulated as securities because the law explicitly says so NOT BECAUSE OF HOWEY TEST

The ruling imposes stricter regulations on sales involving sophisticated institutional investors while relaxing regulations for less sophisticated retail investors. That is backwards. Conventional wisdom prioritizes greater protection for retail investors.